Artistic and historical notes about the Bishop’s House

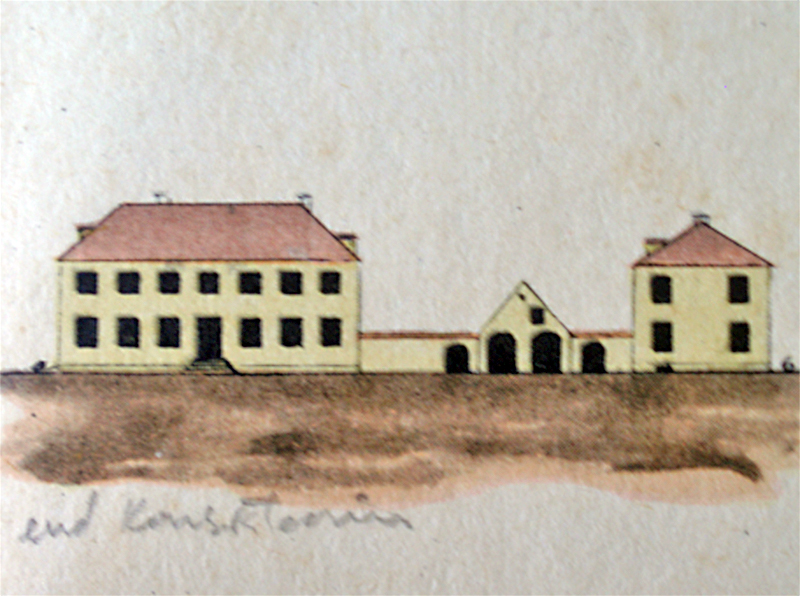

It is not known why or when exactly the first bishop moved to this plot, located on the southern side of the square in front of the Dome Church. It is very likely that a building located at the spot of the current Bishop’s House was used as the residence of the Consistory, established in the 1630s, and of Bishop Joachim Ihering, appointed in 1683. What is certain is that this house was used by Nils (Nicolaus) Gaza, the city’s superintendent and senior pastor of the Dome Church (1604-1638). This Bishop’s House of the ‘Swedish’ period was a stone building with two floors and a high, pitched roof, with two adjoining wings on the southern side. All these buildings were destroyed in the Toompea fire of 6 June 1684.

The construction of the new Bishop’s House progressed slowly, as the main focus was on rebuilding the burnt Dome Church. With a changed position and floor plan compared to its predecessor, we know that one wing of the ground floor was habitable in 1688. It is likely that the final completion of the Bishop’s House was delayed until the second decade of the 18th century due to the Great Northern War.

The new Bishop’s House, with a floor plan and layout that has been mostly preserved until today, was built utilising the basement walls of the previous medieval building, on which we have no information, and the basements themselves also remained in use with some modifications. The stern and functional exterior of the building was dominated by the large windows of the two main floors and the imposing front door with high stairs on the axis of the front façade; a hipped roof provided the building with a significantly different look than it has now. The ground floor layout included a vestibule, typical for a Baroque residential building, a kitchen with a mantle chimney and rooms surrounding the kitchen. The first floor had a roughly similar room layout. The second floor was used for storage, as evidenced by the exposed winch beam and the winch girder protruding from the western gable. Fittingly for a wealthy owner, the beamed ceilings and some walls of the rooms were decorated with murals, dominated by the lush acanthus leaf motif, characteristic of the era. The notable details, which have been preserved from the Baroque Bishop’s House, include the beautifully forged variable corner hinges and hinge pins of the ground floor windows of the front façade, the knob handle and knocker of the front door. The Baroque plate and ram horn hinges are still performing their function on the two interior doors of the first floor.

For the most part, the described form of the Bishop’s House persisted until the last quarter of the 19th century. The modifications made at that time included replacement of the old roof, with demolition of the eastern gable and significant lowering of the roof slopes. The window openings on the ground floor were narrowed and the front door was relocated from the façade axis to the current position. The space under the mantle chimney, which was no longer required, was covered with a brick arch. Many artistically valuable elements were added to the Bishop’s House in the 19th century, such as the carved rafter tips, the front door with a massive box lock, the interior doors in the eastern wing of the ground floors, various window fasteners and finally a wall cupboard – an example of masterful joinery – which some researchers have also dated to the 18th century.

For the most part, the described form of the Bishop’s House persisted until the last quarter of the 19th century. The modifications made at that time included replacement of the old roof, with demolition of the eastern gable and significant lowering of the roof slopes. The window openings on the ground floor were narrowed and the front door was relocated from the façade axis to the current position. The space under the mantle chimney, which was no longer required, was covered with a brick arch. Many artistically valuable elements were added to the Bishop’s House in the 19th century, such as the carved rafter tips, the front door with a massive box lock, the interior doors in the eastern wing of the ground floors, various window fasteners and finally a wall cupboard – an example of masterful joinery – which some researchers have also dated to the 18th century.

A separate chapter in an art history review of the Bishop’s House should be dedicated to the ceiling and wall murals, with fragmentary traces of numerous layers revealing a fast-changing world of interior design arts. We can find traces of previously mentioned Baroque murals in many rooms of the Bishop’s House. The most popular motif of the time – tropically lush plant ornaments – originally covered the beamed ceilings, window and door lintels, window cheeks and, rarely for Tallinn, also the circumferences of door openings. As a result of changing fashion, the interior design of many rooms was probably renewed as early as at the end of the 18th century. For instance, several ceilings were covered with a distinctive paint cover resembling stucco lustro. The 19th century saw numerous interior redesigns, with a series of new murals painted over or even in place of the old ones. During this century, the figural friezes of the Bishop’s House were decorated with angels, lions and basilisks – they are all still visible today after thorough restoration.

A separate chapter in an art history review of the Bishop’s House should be dedicated to the ceiling and wall murals, with fragmentary traces of numerous layers revealing a fast-changing world of interior design arts. We can find traces of previously mentioned Baroque murals in many rooms of the Bishop’s House. The most popular motif of the time – tropically lush plant ornaments – originally covered the beamed ceilings, window and door lintels, window cheeks and, rarely for Tallinn, also the circumferences of door openings. As a result of changing fashion, the interior design of many rooms was probably renewed as early as at the end of the 18th century. For instance, several ceilings were covered with a distinctive paint cover resembling stucco lustro. The 19th century saw numerous interior redesigns, with a series of new murals painted over or even in place of the old ones. During this century, the figural friezes of the Bishop’s House were decorated with angels, lions and basilisks – they are all still visible today after thorough restoration.

Politics was the decisive keyword for the history of the Bishop’s House in the first half of the 20th century. Having been expropriated by the Ministry of the Interior in 1920 as part of the property of the fiefdom, the building was assigned a new status with a decree of the Head of State in 1934, giving the property to the EELC.

On 20 August 1940, the Bishop’s House was forcibly taken over by the Soviet Army. In November 1941, the Bishop and the Consistory managed to move back to the building for a brief period, but the events of August 1940 recurred again in three years. The last list of residents of the Bishop’s House dates back to 1944. The two official apartments were used by Bishop Johan Kõpp and his family and the janitor with his family.

On 20 August 1940, the Bishop’s House was forcibly taken over by the Soviet Army. In November 1941, the Bishop and the Consistory managed to move back to the building for a brief period, but the events of August 1940 recurred again in three years. The last list of residents of the Bishop’s House dates back to 1944. The two official apartments were used by Bishop Johan Kõpp and his family and the janitor with his family.

After the war, the Bishop’s House was first used by the Russian military intelligence service and then redesigned as a residential building with multiple apartments and the condition of the building deteriorated due to haphazard reconstructions and lack of an owner. Having been returned to the church after restoration of Estonia’s independence, the renovation of the Bishop’s House concluded with its re-consecration on 12 February 1994.

Juhan Kilumets, art historian